All estimates are wrong. Some are useful.

The planning fallacy always wins

Why estimate?

Estimates are useful ways to communicate the challenges around different pieces of work. By helping a team to understand the problem space, they can consider how they might approach it and give an indication of effort. This can help with prioritisation and trade-offs.

It’s a useful way of doing an early cost-benefit analysis. An estimate of effort for a new experiment or product capability (the cost) can be compared with the benefit (which should form the basis of the Product Manager’s hypothesis). It’s an early sense check on the viability of pursuing the solution.

Estimates also enable the organisation to make decisions about trade-offs. There are only ever a finite number of people available, and there are multiple ways the organisation can choose to deploy them. Understanding the level of effort, the likely cost-benefit, and time to market helps stakeholders and leaders to decide which initiatives they want to back.

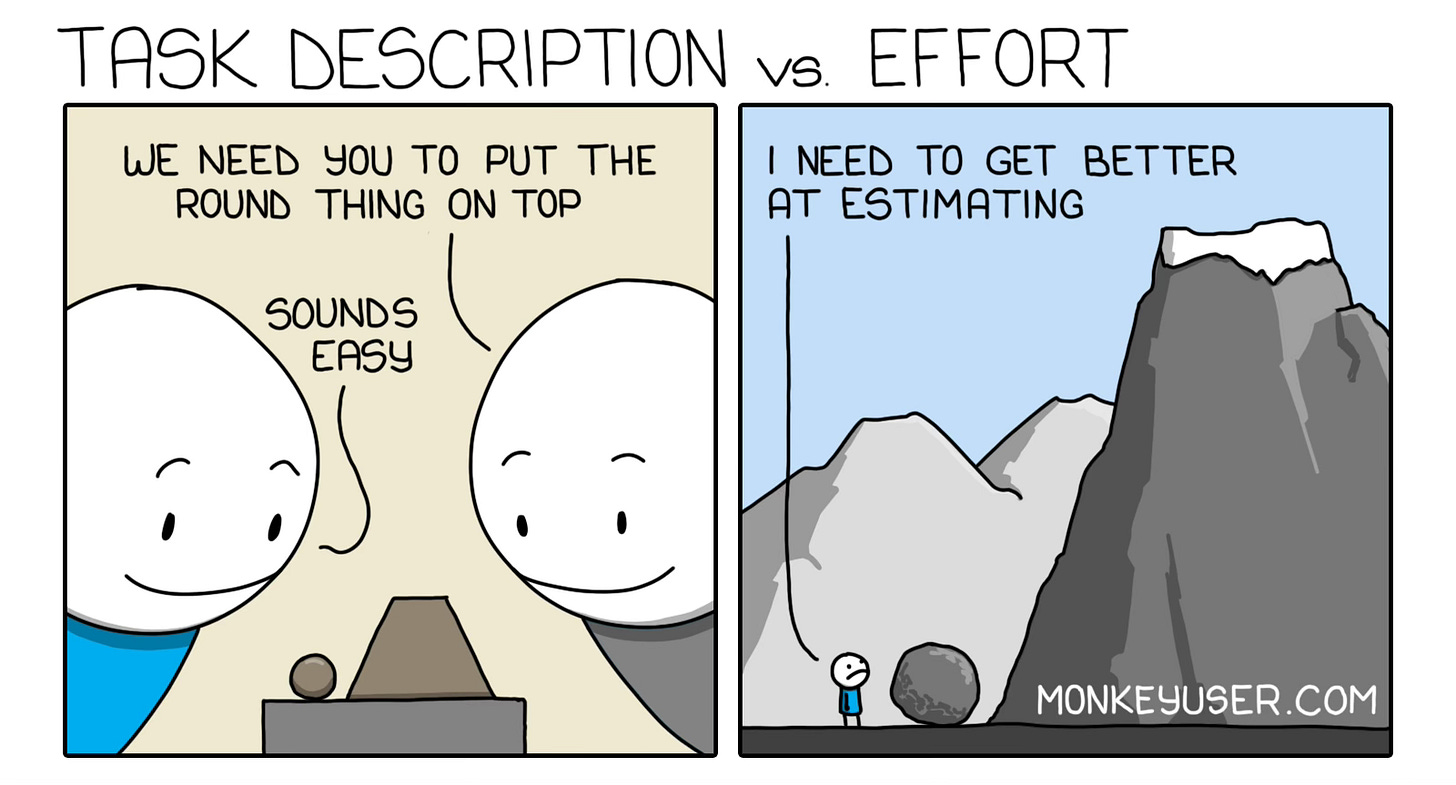

An estimate gives the team the opportunity to examine the shape of a solution and to get aligned around it. If the Product Manager believes they’re asking for something straightforward and the team estimates it at 6 - 8 months of work for 3 - 4 teams, this surfaces a difference in expectations early and cheaply. It’s possible that the Product Manager is underestimating the complexity of the problem. It’s equally possible that the team has misunderstood or misinterpreted the ask. Either way, there’s an early signal to ensure that the assumptions all sides have made are captured and corrected as appropriate.

It’s a snapshot

Recording these assumptions is paramount. An estimate is a snapshot. It’s a statement of current understanding. By recording assumptions and open questions, the team can indicate what it knows and what it doesn’t. An estimate can always be revised in the light of further information. I’ve seen estimates revised down from weeks to days of work as discussions surfaced different solutions and gave clearer definition of the problem being solved. Equally, we have to be prepared for estimates to grow as more information becomes available. For example, a team working on a novel solution may encounter unforeseen problems or have blind spots that mean they will have to re-estimate as they encounter these.

All estimates are wrong.

The most important thing that anyone can know about any estimate is that it is wrong.

Estimates are best guesses about the future. Like all guesses, they are subject to biases. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky coined the term ‘planning fallacy’ to account for the fact that people tend to focus on the happy path, and ignore the likely obstacles and distractions they will encounter along the way. This fallacy occurs even when people have knowledge and/or prior experience of the complexity of the space.

How does this manifest itself? It goes to the very heart of the way we estimate as humans.

Let’s say an engineer looks at a problem, considers the steps they would take to solve it, and they come to what Kahneman and Tversky call an ‘inside view’ that it will take 2 - 3 days.

Even when shown data (the ‘outside view’) that a similar problem took them 3 - 4 weeks to resolve, the developer is likely to continue to under-estimate the complexity of the task, sticking close to their original estimate. People ignore or undervalue objective evidence like this again and again. It’s a deeply ingrained behaviour. The reason that quests for ‘better estimates’ fail isn’t because people don’t understand data. The case-specific information they’ve generated about this task feels more relevant and concrete than any historic or statistical data, and they cling to this rather than taking a data-driven approach.

Attempts to combat this error by adding a slippage factor are rarely adequate, since the adjusted value tends to remain too close to the initial value that acts as an anchor. - Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, Intuitive Prediction: Biases and Corrective Procedures, 1979

Let’s imagine that our fictional engineer is estimating the effort to update an authentication flow. They consider that they need to build some new forms with input validations, and a method for recording the user details in the back end. “2 - 3 days, considering some of the other work I’ll have to do.”

As they actually do the work, reality dawns. There are gaps in the original requirements, including rules around password difficulty, and a handle forgot password flow. They get interrupted by production issues. There are some underlying libraries that need upgrading, along with some security updates. The original design didn’t have complete accessibility and responsiveness requirements. Some edge cases get raised when testing the new form, and there’s a downstream integration that starts failing because of the new flow. They have to write supporting documentation. A month goes by before the change finally makes it to production.

Do we think they’ll ‘improve’ their estimate next time? The evidence suggests that they won’t.

Along with the happy path planning fallacy, people tend to forget the other commitments they have competing for their time. A developer might estimate “four days” of coding while forgetting that they have six hours of meetings that week, a training course to attend, will need to wait for code review, and historically spend 30% of their time on unplanned work. That’s before we add in the need for design work and testing.

The longer that a task may take, the less likely an estimate is to survive contact with reality. As we look out across the cone of uncertainty, the further into the future we project, the less likely we are to have considered the probability of distractions and obstacles.

Some are useful.

Being aware of the inaccuracy of estimates doesn’t mean they’re useless. It means we need to use them with caution. They have a role in rough cost-benefit, or for guiding conversations about alignment or choices. What they shouldn’t be used for is planning.

Given that we know that teams will fail to account for complexity and unforeseen events, using a t-shirt size or an estimate of effort as a commitment is a mistake organisations make time and again. Years of effort are wasted on ‘improving’ estimates. Setting aside the language for a moment (‘improving’ is usually code for ‘shortening’), it’s a fight against reality.

Organisations often introduce more planning sessions, or introduce scaled agile frameworks to improve predictability. But these frameworks are no match for the cognitive biases hard-wired into human thinking. Calibrating story points, or arguing over how to reduce a XL t-shirt size to a L doesn’t deliver any value to the organisation. It just creates the illusion of certainty and reduces psychological safety. The team spends time trying to fit the work into an acceptable plan, instead of thinking about the most valuable work and finding ways to test their assumptions early and reduce uncertainty.

Reality always wins. The biases that lead to inaccurate forecasting occur time and again, even when we’re aware of them. We can only escape this trap if we use forecasts for what they are genuinely useful for - decisions around relative complexity or priority. Then we need to design the work so that we can falsify any hypotheses we have as cheaply and as easily as possible.

So well said, Andrew!

Fantastic points made about how estimates are treated by organisations, and how teams have a happy path bias. Even when the data from previously completed work shows the same patterns occurring, we are loathe to revise estimates upwards.

Which leads me to your other observation that ...

"An estimate gives the team the opportunity to examine the shape of a solution and to get aligned around it." If only!!

Instead it seems the real-life experience is often "an estimate is the 'correct' answer for a mathematical equation that leadership knows in advance, but which teams get 'wrong' repeatedly because they insist on following the rules of addition and multiplication." Eventually though the team get ground down to agreeing to a date (usually by cutting scope or quality) .... BUT those undelivered items or resulting bug fixes never make it into the next estimate.

The bane of my life for "quarterly planning". Plus as you rightly pointed out, people neglect factoring in other commitments like training or holidays or customer critical support. Those "don't count," and yet they do.

Rant over.