Commitment-phobia

Agile swear-words part 2

The only f-word I won’t say: Agile swear words part 1

I was in a planning session where we were reviewing a customer request. Our proposed solution was well-understood. It was very similar to work we’d done before. We were confident that we could deliver quickly and we started to lay out a plan.

“So we’re making a commitment to deliver by this date,” said the Sales Manager, picking the earliest date she’d heard in the conversation.

Not even a little bit.

“Based on what we know today, we believe that we can achieve this outcome in roughly this amount of time (between x and y days).” I responded.

“We have to make a commitment,'“ she said.

“Would you bet your salary that we’ll deliver by x?”

A long pause.

“Well, there are some things that might go wrong…”

The illusion of certainty

There is an understandable need to give stakeholders and customers an idea they can anchor their own plans around if they’re waiting for a particular problem to be solved. Marketing campaigns are built on the promise that work will be delivered.

This doesn’t automatically translate to a statement of firm dates.

Dates can be an interesting forcing function, meaning you have to focus on the scope of what can be delivered or a tactical solution that will enable you to get a solution in place. But they shouldn’t be the sole driver of development.

This isn’t like a wedding or an event you book months in advance where you know the date and put in place plans to suit. In software development, you have some idea what you need to build and a lot of uncertainty around what can happen between now and when that work will be complete.

Breaking things down into smaller chunks can reduce your uncertainty, but there’s little to be said for trying to be overly precise

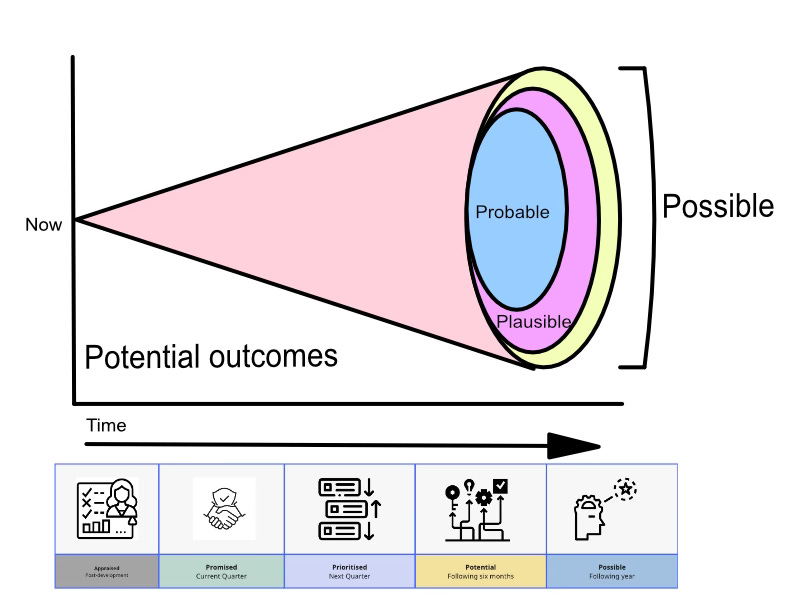

Some teams spend huge amounts of efforts trying to improve their estimates, but the reality is estimates will always be off. Teams have multiple commitments, something often comes up after the work starts, etc. Why pretend to know the future, when the Cone of Uncertainty tells us we can’t have complete knowledge about what will happen?

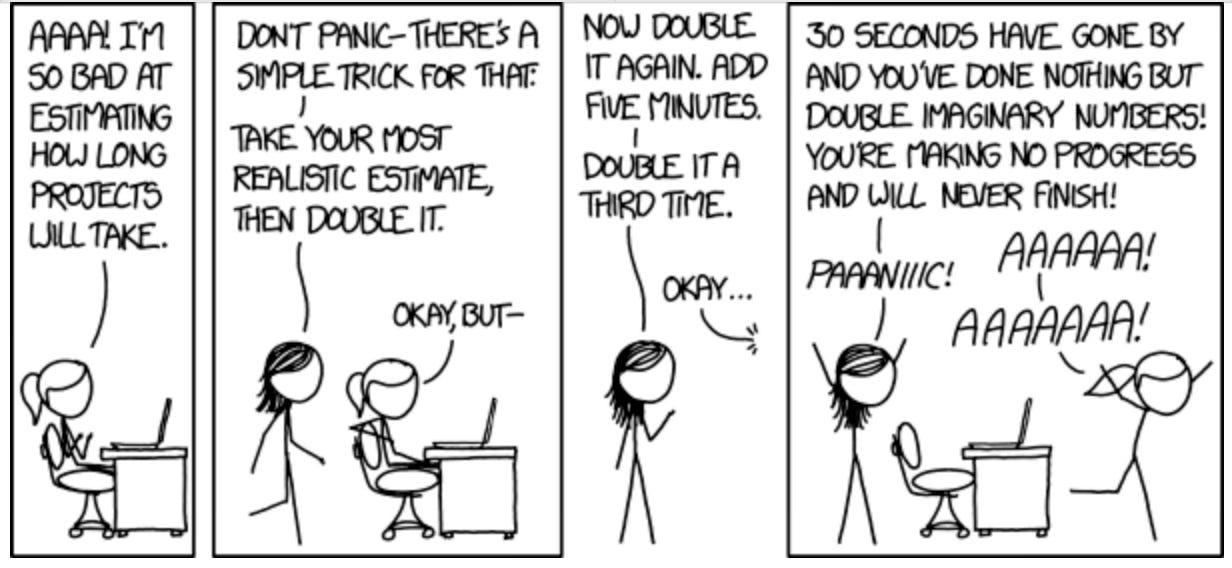

Moreover, people are notoriously bad at giving estimates. Almost everyone is an optimist when thinking about how hard something might be. Engineers forget to include testing or any of the things that might go wrong. Product managers may add some contingency, but given the level of uncertainty, particularly for larger or long-lived pieces of work, they may be the bearers of bad news in the short-term (“this is going to take a while") or the long-term (“I know I said this wouldn’t take long….”). Neither is a position that they really want to be in.

It’s about this size….

Rather than speaking about commitments, we should acknowledge that uncertainty and give ranges with confidence intervals. T-shirt sizes can be a good shared language for this, where you can say (something like):

XS < week

S < 3 weeks

M < 5 weeks

L < 8 weeks

XL > 8 weeks

When it comes to confidence interval, the question is: “How much do I believe this will work.” If this is a well-defined piece of work, similar to something the team has done before, you can have a higher degree of confidence than if you’re grappling with something completely new.

It can take some getting used to, but if you can be 90% confident you can deliver a solution in 2 -3 weeks, then there’s enough for you to give a t-shirt size of S-M, saying “I’m 90% confident this is a S, and there’s a 10% chance it may become an M.” This gives some certainty around delivery, but also acknowledges the impact if your initial estimate is off. This gives a range in which you think delivery is possible. If a PM really needs a date, they can take the worst-case scenario, or tell the customer “we’re 90% confident it will be done in 3 weeks.”

Worst dates

What you need to avoid is a fixed-scope, fixed-date, fixed-quality conversation when you know that you’re operating in uncertainty. You may hit an unanticipated issue that means your proposed solution design won't work. You may have a production outage or service interruption that takes the team’s attention away for a period of time. Even a short interruption causing context-switching can have an outsized impact.

Giving a commitment in these circumstances is laying a trap for yourself. You may be lucky, stay on the happy path, and everything turns out as predicted. In which case, nobody will remember you wouldn’t commit to a date for delivery in the first place. If you have made an incorrect assumption, or if there’s an issue of any sort, you’re instantly under enormous pressure.

As a result of this, commitment conversations can have the opposite-to-desired effect, as teams are incentivised to under-promise. The stakeholder’s desire for increased velocity backfires as the team learns to avoid risk.

Have more than one conversation

A mistake teams often make is not updating stakeholders on progress, particularly as they learn how wrong their initial estimate was. If they discover something that blows up their initial estimate, it’s best to communicate that early, along with an explanation of the issue. There may be contingencies they can take. If at all possible, they should look to stagger delivery so that progress is visible to all, building confidence in the team.

In summary, accept uncertainty

Commitments are unbreakable, or they lead to failure. When a date becomes the target, teams can end up under delivering something sub-optimal to a date instead of being able to figure out the best solution to a problem and deliver it as quickly as possible. Once a product team makes a commitment, they’re on the hook for all the things that can go wrong, inside and outside their control.

There’s nothing wrong with making forecasts. Why make commitments?

Don’t say

We commit to making a full delivery by this time.

Do say

We have agreed that this is the problem that we’ll solve. Based on what we know now, we believe we can have something for you to look at around this time, and we’ll work with you to get a working solution in production as soon as possible.