The urgency-industrial complex

Updating the Eisenhower matrix for reactive strategy

The beautiful moment

Last week, I read Strategy & Urgency by John Cutler and a light came on in my brain. I’ve been one of those people who gripe about a lack of strategy at organisations where I’ve worked. At various times, my complaints about prioritisation or lack thereof, have been long and loud.

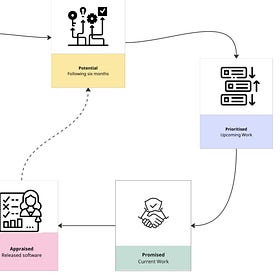

I’ve seen plans made, only to be abandoned almost immediately. Strategies with a half-life of hours. Being able to bring order to chaos was one of the drivers of creating the PandA framework. I loved the idea that we could embrace uncertainty and focus on the future in a way that allowed us more control.

PandA

Product teams are expected to deliver on time and innovate, to stay aligned and be autonomous, to be accountable for outcomes while being rewarded for output.

But, I realised as I read the Cutler article, what if the company strategy is reactive by design? The old lament of “fail to plan, plan to fail” doesn’t stand up if leadership’s core bet is that responsiveness beats consistency. For the right opportunity, planning will be turned on its head, and the organisation will pivot completely.

In the absence of an explicit strategy, the implicit strategy is maximum agility. - we will always respond to the most urgent problem.

Each system is perfectly designed to give you exactly what you are getting today. - attributed to W. Edwards Deming

If that’s the case, why not intentionally leverage for it? Let’s not waste time in detailed strategic planning, or talk about what we “will” do. We can plan and ensure we talk about intent, while accepting things might change in an instant. Let’s embrace the uncertainty. Let’s welcome the urgency.

Shaping our choices

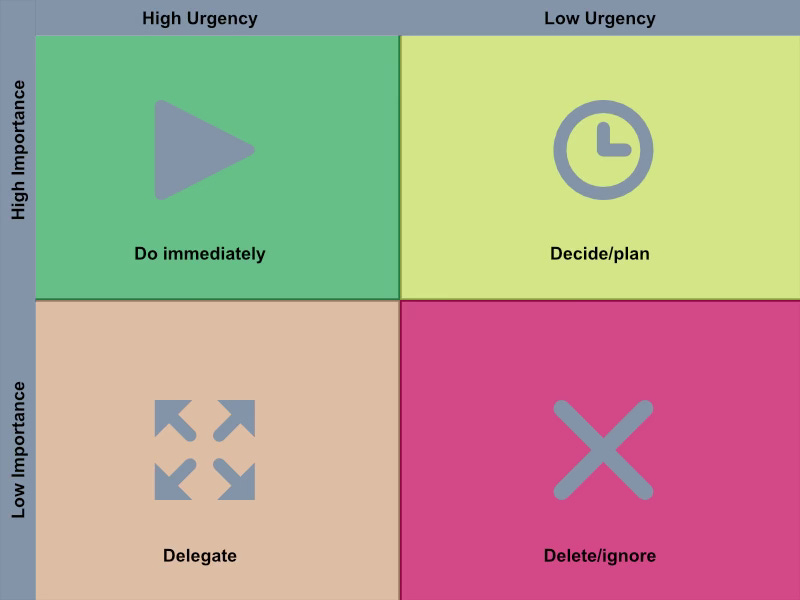

How should we think of planning in an organisation where the strategy is reactive? We need an updated Eisenhower matrix.

The Eisenhower matrix is a prioritisation technique using a 2x2 diagram to rate tasks based on urgency and importance.

Urgent tasks are those which require immediate attention. They have a deadline or an imminent consequence for non-completion, e.g. a serious customer issue or complaint.

Important tasks don’t have the same immediacy, but will help achieve longer-term goals, e.g. developing strong customer relationships.

Traditionally, the Eisenhower matrix groups tasks into the following quadrants:

High urgency/high importance: do these tasks first

Low urgency/high importance: decide and prioritise

High urgency/low importance: delegate the task to get it done

Low urgency/low importance: delete these tasks from your to-do list.

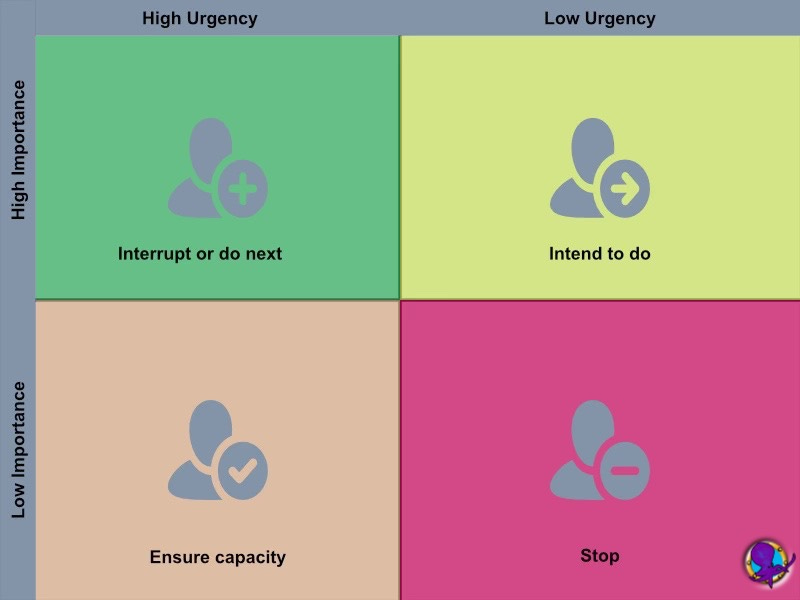

If we take an organisational view of this, assuming that we have a reactive strategy, we can create a new Eisenhower matrix, that takes account of how prioritisation really works, and gets everyone on the same page.

Quadrant 1: High urgency/high importance

By definition, a high-urgency task must have a pressing deadline. If it is also of high importance, it is going to the front of the queue. It’s either going to interrupt teams, or it’s going to displace their next upcoming task.

In many cases, these tasks become high urgency and high importance because they’re not considered high-importance until they become urgent. For example, a product capability could be sitting on a team’s backlog for years, never prioritised, until suddenly it becomes critical to a large customer renewal.

Other examples include:

Service interruptions

Contract or sales commitments that only become visible late-in-the-day

Security vulnerability remediation

Quadrant 2: Low urgency/high importance

These are the tasks that exist in most organisations planning sessions. These are the things we intend to do assuming that we don’t get interrupted. This is where your product roadmap lives.

It’s still important. You just have to be prepared for it to be interrupted.

Examples of Quadrant 2 activities include:

Planned product capabilities

Technical investments

Developer productivity initiatives

Quadrant 3: High urgency/low importance

These are tasks that have deadlines but are routine or are unlikely to have a wide impact on the business. There’s a need to ensure that sufficient capacity is reserved to enable these tasks to continue uninterrupted. Any non-routine tasks falling into this quadrant should be small in scope.

Examples include:

Financial reporting and company filing

Preparing marketing materials for a pitch to a smaller client

Readying a presentation for a board meeting

Quadrant 4: Low urgency/low importance

Ideally, these are tasks that the organisation would drop, but often take up time.

Examples include:

Refactoring or optimising lightly-used code

Meetings that don’t have clear agendas or outcomes

Adding unvalidated product capabilities to the backlog

So, how would it operate?

Quadrant 1 tasks will continue to interrupt Quadrant 2 plans.

I’m not arguing for a change in the way a reactive organisation does business. I’m pleading for us to change the way we think about it. Rather than complain about how a large customer request suddenly becomes the most critical thing the organisation faces, we recognise what’s happening using the updated Eisenhower matrix.

It’s a mindset shift. We’re basically saying “We know we might be interrupted, and that’s ok.” We plan in Quadrant 2, but we’re going to live in Quadrant 1 a lot of the time.

Thankfully, we already have a system for this - kanban. This new, reactive Eisenhower matrix maps naturally onto the pull-based approach of kanban. As a large quadrant 1 task comes in, it naturally displaces the next-most-important Quadrant 2 task. Kanban’s visualisations at different flight-levels would ensure alignment at all levels in the organisation about the work being moved.

Instead of torturing ourselves with quarterly or annual planning sessions (for quadrant 2) that only lead to frustration when a large quadrant 1 task comes in, we can adopt a more flexible framework that allows us to be resilient.

Are you saying we shouldn’t plan?

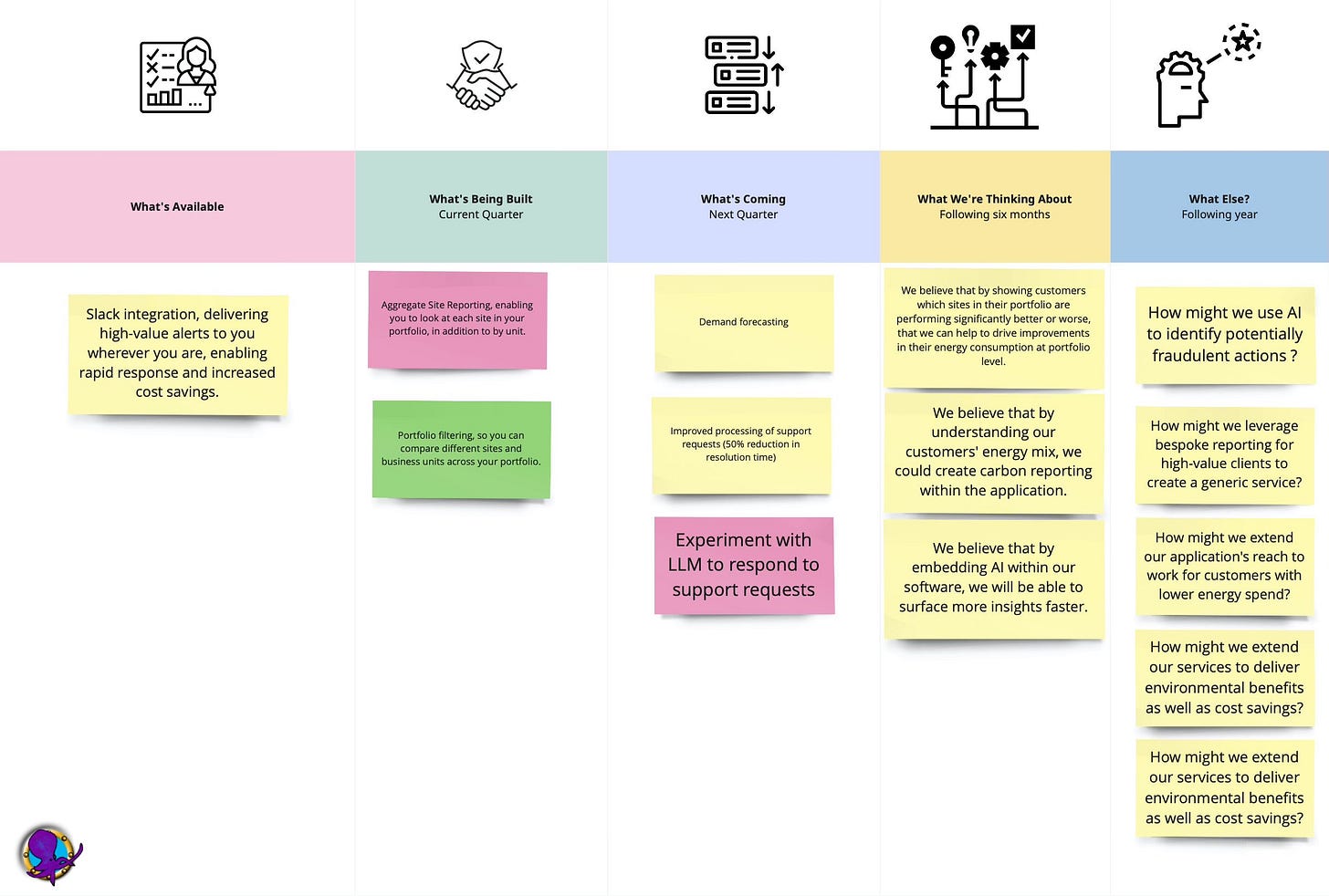

Not at all. The organisation should still plan, but this plan shouldn’t be fetishised. It’s a statement of intent, but the core strategy remains one of reactivity. We can still set OKRs to determine a sense of direction and how we will measure success. We can use PandA or another framework to plan and manage Quadrant 2 tasks. But instead of investing weeks of time over a year in planning, we should take a lightweight approach, recognising this is work that we intend to do, but may not. Interruptions can be welcomed in this world.

How do we get out of this reactive world?

I wrote here before about the need for cross-functional collaboration and making product roadmaps a shared enterprise. If you get better communication between Sales, Marketing and Product, you can move from a reactive to a proactive posture. You can plan for various scenarios based on information from customers, prospects, and the wider market. This takes time, intent and leadership buy-in.

Do you wanna?

But your organisation may have chosen reactivity as its strategy. It may never have been explicit, but if your leadership values rapid response to market changes or customer demand, sometimes ripping up plans as soon as they have been made, then what appears to be the absence of strategy may more accurately be described as a strategy of embracing uncertainty.

If you’re working in an organisation where it feels like ‘surprises’ keep happening, that leadership creates artificial urgency, or that it’s harder than it should be to improve and harden processes, here’s the good news. Your organisation is not dysfunctional. It’s reactive by design. This was my lightbulb moment.

It may feel chaotic. Frustration will get you nowhere. Reality always wins. You can win too, one quadrant at a time.

Excellent piece . This has been a real lightbulb for me too. I’ve often advocated for better planning only to be frustrated by ripping up the plan. “Responding to change over following the plan” - now where have I heard that before?! The plan is very useful to know what the trade off is when the urgent/important work arises but if the strategy is reactive it should be a light touch, loosely held plan, with no mention of the word ‘commit’!