Three levers for leadership

How autonomy, alignment and accountability can shape organisational success.

“A bad system will beat a good person every time”, - W. Edwards Deming

Every company is a socio-technical system. The results you get are exactly the ones that system is optimised to deliver. You may not like these results, but they’re yours.

Disappointment tends to result in blame games. Some leaders will blame the people who work for them. The people will blame the tools, or the technology, or leadership decisions. All of these concerns are legitimate, but they tend to ignore wider questions about the socio-technical system in which they operate.

What’s a socio-technical system anyway?

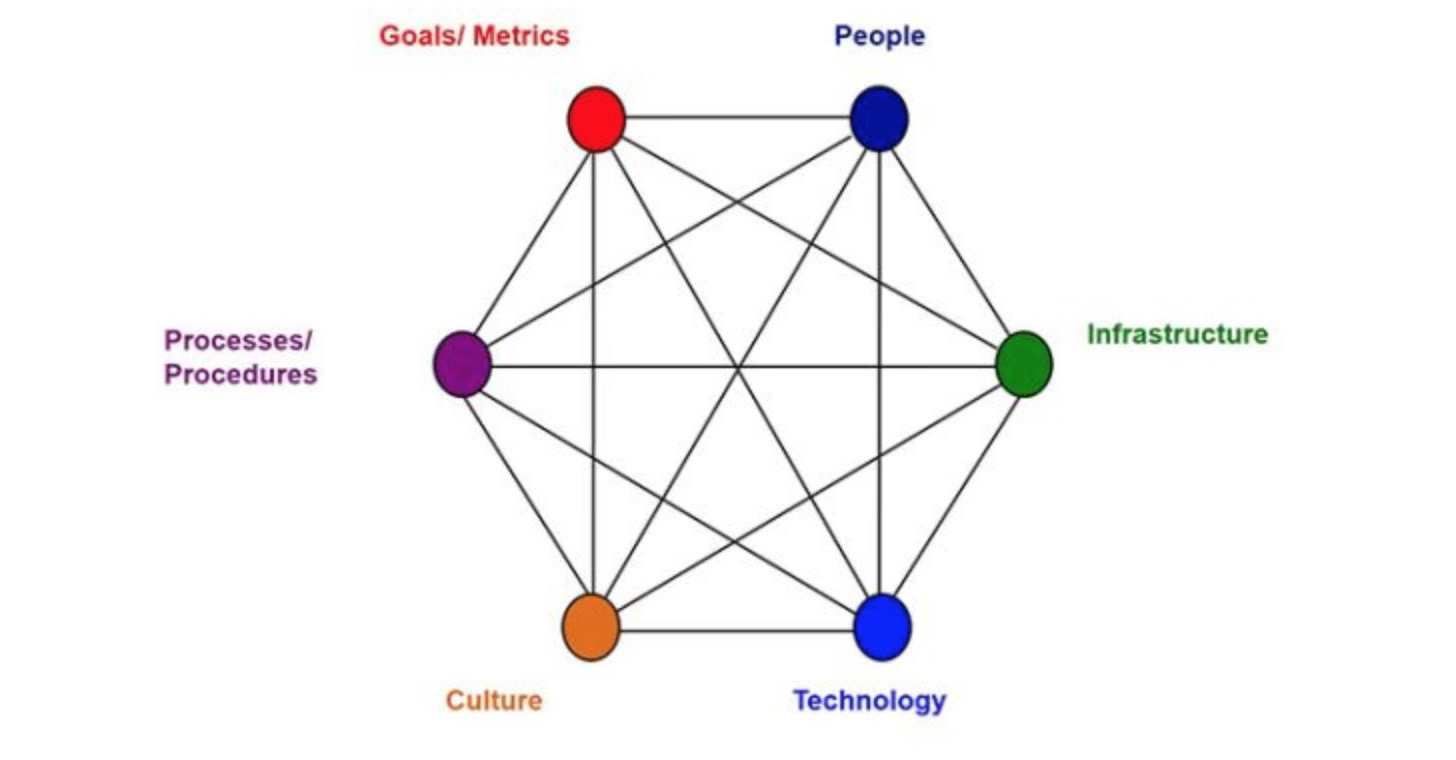

Looking at organisations (or teams) through a socio-technical lens means examining the interaction of various components that make up the overall system. For example, people have goals and use infrastructure, technology and processes to achieve them. The way these interactions take place give rise to culture and behavioural norms. These in turn are informed by the constraints of the other components and by the people themselves. Thinking of organisations as socio-technical systems allows us to consider the complexity of organisational change, and to understand how changes in one aspect can have consequences for other areas.

Every company and every department has its own politics, history, and culture. The technology in use, and the decisions made, inform the system in which people operate. No two sets of circumstances are exactly the same. There is no guarantee that what works for one team in a particular situation will work for another in a similar one.

Or, to put it another way, each software development team is unhappy in its own way.

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. - Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

No ring to rule them all

Accepting that there is no universally correct way of building software should be liberating. We have the opportunity to consider our circumstances fully, which is surely better than blindly imposing solutions on problems that may or may not exist (does anyone still believe in the Spotify Model?).

The concept of best practice is flawed, as seen by companies such as Thoughtworks shifting to the idea of sensible defaults, which allows for the idea that recommended actions may not be suitable in all situations.

If this is true, though. How then can we hope to solve systemic issues?

Rather than seeking to impose the same rules in every organisation, or attempting some cargo cult version of agile, we need to develop a language that allows us to talk about trade-offs in a meaningful and accessible way. Executives are busy people, context-switching multiple times a day. Using language like ‘socio-technical system’ excites nerds like me, but puts a barrier up to them understanding what actions they can take.

What leaders need are practical levers they can use to intentionally shape their organisational system. The answer lies in finding the right level of abstraction. While each socio-technical system is unique, there are three key dimensions that leaders can radically influence.

Three levers

Regardless of culture, technology or scenario, there are three levers the organisation can pull that make all of the difference in how their system will operate.

Autonomy

Accountability

Alignment

Viewed this way, the socio-technical system can more easily be envisaged as a set of trade-offs. The tension created by these trade-offs defines the system in meaningful ways. Let’s discuss these areas and tensions, with some sample questions to define how your system operates today.

Autonomy

Autonomy is best defined as the level of self-determination the team has. A lot has been written about self-organising teams, and some companies have even gone as far as letting employees self-select the teams that they work with and/or the problems that they work on. Research has suggested there may be limits on how far autonomy can be pushed, but groups with high autonomy are by definition high trust. Higher levels of happiness were reported by more autonomous groups in the work published in the Harvard Business Review.

Autonomy may be easier to provide in smaller organisations, with fewer cross-functional dependencies or legacy architecture to contend with. Autonomy can be held in tension with the other two levers, particularly alignment, but accountability is also an important trade-off.

How autonomous are your teams?

How much freedom do they have to decide on their ways of working?

Are they able to deliver software independently?

Do they consistently have dependencies on other teams?

How much influence do they have over their own roadmap?

What sort of decisions can they make without reference to leadership?

Get started

Map out the decisions that your teams can make without reference to leadership or other teams. What does this tell you about their current level of autonomy?

Alignment

Alignment is necessary if a business is going to achieve its goals. While unbounded autonomy may sound attractive, there are always some constraints. For example, nobody wants a Sales team to sell a product that they don’t have the capacity to build. Equally unattractive outcomes await a software team that decides to unilaterally develop a completely different product to that agreed to with stakeholders and for which there’s no market.

Alignment constrains autonomy, and that tension cuts both ways. The aim is to find the right balance between needing teams to work together (particularly in larger organisations) and in enabling teams to discover and experiment so they can be most productive. Being conscious of this tension and the impact of the trade-offs you make is vital, and it’s worth maintaining an open mind on this and continuing to calibrate the organisation to ensure you continue to get the results you want.

Accountability is an important consideration for alignment. It should be clear who is responsible for delivering cross-cutting work. That person should also have the authority to be able to direct the necessary work across aligned areas.

How aligned are your teams?

Do your teams understand the organisation’s goals?

Do they understand what success looks like for the organisation and how their success is expected to contribute directly to it?

Is there a consistent interpretation of success?

Is there a shared understanding of organisational priorities?

Do you have teams that regularly forego work in their own area in order to support wider company initiatives? Is such activity resented or supported?

Get started

Ask everyone in the team how their work rolls up into the organisation’s wider goals. Who is their customer? Who do they depend upon? Do their answers match your understanding? Do they match leadership’s? Ask yourself what steps do you need to take to calibrate this so everyone is aligned.

Accountability

Accountability is often interpreted as ‘who gets the blame if things go wrong.’ This is unhelpful to building a trusting environment where teams are able to be autonomous or ensuring that alignment is valued.

Accountability is better thought of as who owns what, and by how much. This definition illuminates its relationship with the other two levers.

Accountability should result from the level of autonomy people have, and the clarity of alignment to wider goals. People should not be held accountable for results when they have limited control over other aspects of the system. For example, if a team is told to work on something, handed designs and told to deliver output, it’s hard to see how they can be held accountable for the resulting outcomes. If teams are misaligned, then who is accountable for that?

Accountability is an important lever for leadership, but it’s important that leadership hold themselves accountable for results, as well as looking at the people below them.

A note of caution: trying to “hold people accountable” without first ensuring that you are designing for autonomy and alignment is likely to result in less accountability and autonomy as people will react from fear, rather than from alignment with your goals.

How accountable are your teams?

Is there broad agreement on what success looks like for the team and organisation?

Do the teams understand how success should be measured?

Are they able to run discovery and experiments to validate assumptions?

Do teams feel responsible for their success?

Do they have complete control over their development process and deployment lifecycle?

Get started

Ask the team who gets the credit when things go well, and who gets the blame when things go wrong. Review their retrospectives to see if they are holding themselves accountable. What does this tell you about accountability and trust within and beyond the team?

Interdependency matters

If you think of your organisation or your team as a machine, you can use these three levers to control its performance. The levers are interdependent. Remember that you will need to adjust the settings for different contexts, and even for different-sized organisations or initiatives.

In smaller teams and startups, autonomy and accountability tends to naturally align. There’s little need for formal structures to keep everyone focused on the goal. As organisations grow, and system architecture becomes more complex, alignment moves into tension with autonomy, and accountability can become unclear. In larger organisations, there tend to be formal processes and procedures that constrain autonomy, and are supposed to deliver accountability and alignment, but these systems’ very formality often put them in opposition to the organisation’s actual needs.

You can move beyond the blame game and intentionally design your system for better outcomes. Get started by being curious about autonomy, alignment and accountability. Ask questions. Pull the levers. Take control.