Shipping isn't working

Why product adoption doesn't tell you whether your software works

Hard lessons

You’ve shipped your startup’s first product, or you’ve added something cool to your mature product. The months of research, experimentation and development have paid off. Adoption is strong. Customer feedback is good. Revenues flow in.

Your product features in a major tech news article. Usage spikes 20x overnight. Time to pop the champagne, right?

Before you have a chance to roll out the ice buckets, your application crashes.

It simply wasn’t designed to cope with the loads you’re experiencing.

Everyone assumes an engineering issue.

But the post-mortem reveals that load testing was never prioritised. It wasn’t included in the requirements. When timescales tightened before launch, testing was scaled back. The PM signed off releasing the product without ensuring that it worked reliably in production. This is a product failure.

Mind the gap

Product managers often begin and end with functional requirements. Non-functional requirements like performance or resilience get relegated to “engineering concerns.” But if the product organisation values delivery over reliability, then reliability and resilience usually end up becoming “technical debt.” This is a category error. Acceptable levels of uptime and latency directly impact the customer experience. Pushing for ‘quick’ delivery over robust engineering practices leaves a huge gap.

Common examples of how this happens include:

Done is defined as ‘feature-complete’ (a phrase I hate), or ‘it works in staging,’ with little or no consideration of how the software will perform in the wild.

Product launches are celebrated. Product ownership is ignored. The product team becomes a feature factory, churning out software, with little time or incentive to worry about coherence or performance. This can be exacerbated where the team is not responsible for supporting the product once it goes live. The tax of bad decisions falls on support, not on the product team.

Engineers or QAs are expected to consider edge cases or things that can go wrong. Product Managers define the happy path and then abdicate responsibility.

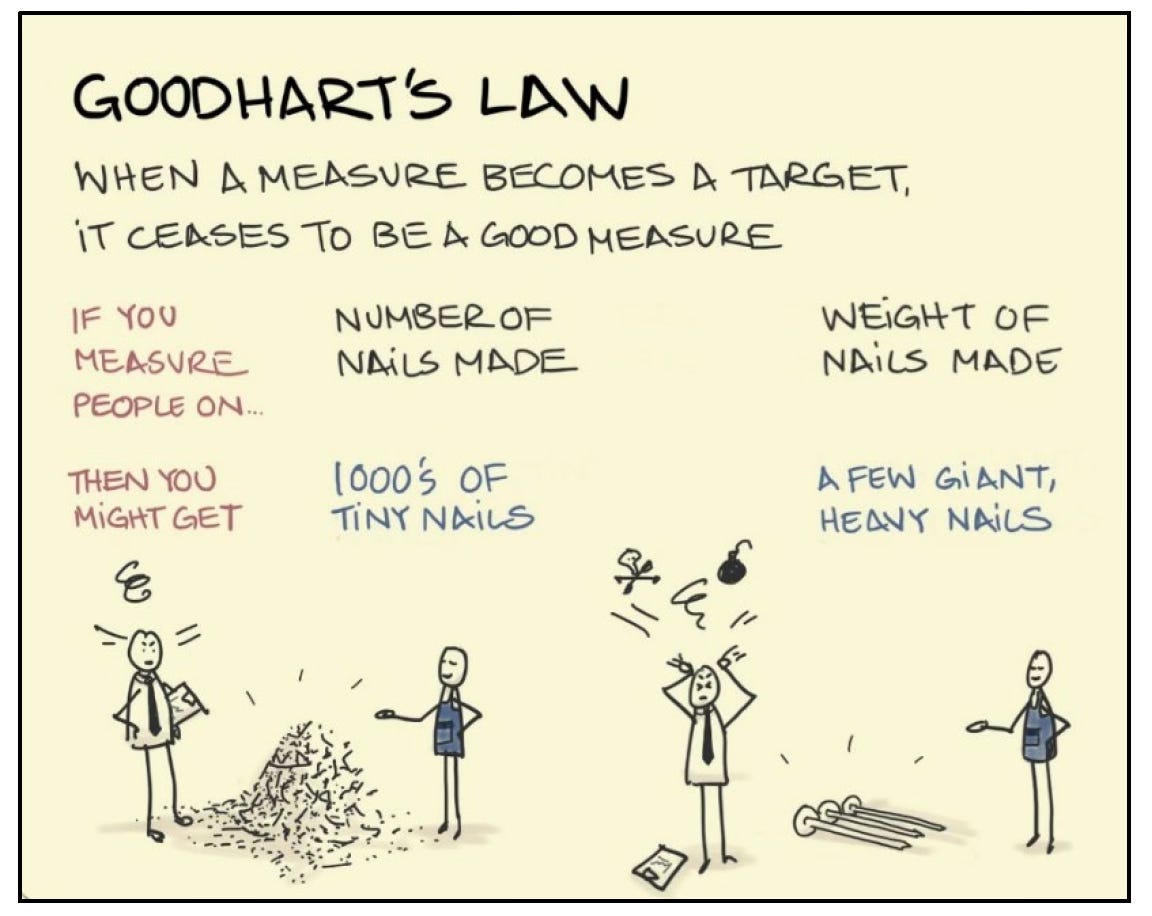

The company doesn’t have centrally-set performance benchmarks, leading to either local optimisations, or perverse decisions. I’ve heard of more than one case where a team refused to set a performance target until they had performance tested, and then decided that the result was the target. An interesting inversion of Goodhart’s Law, but not one that is likely to deliver the right type of customer surprise, and certainly not delight.

Goodhart’s Law, illustrated. Image source Product hypotheses focus on adoption, e.g. 15% uplift in engagement, but not on resilience, e.g. handles 10x traffic spike. Without company benchmarks, performance requirements are never made explicit, which means you can’t appraise whether your software actually works.

Product dashboards measure things like adoption and satisfaction, but they don’t extend to measures of reliability, such as latency or error rates. Activities that can highlight issues around resilience, such as chaos engineering or game day testing are never scheduled.

In other words, performance is overlooked, or sacrificed on the lie that you’re shipping a MVP and you’ll come back to it later. The risk is the first that you will learn of any failure is when a customer complains about it, either directly to you or on social media.

Fill the gap

Closing this gap is an organisational obligation.

Your organisation needs defined standards of:

Acceptable uptime: do you have a three-nines (99.9% available) or five-nines (99.999% available) product? Are there different product tiers with differing standards?

Latency standards: what’s acceptable for real-time interactions, page loads, analytics calculations? What is the customer experience where a particular query is going to take several seconds to complete?

Resilience: how does the application handle scale and spikes in demand? Does it fail gracefully when data services or dependencies go down? What messaging is given to users when they encounter issues? How granular are your logs?

Security: do you penetration test every new product capability? Do you undertake regular vulnerability scanning? What are your policies for addressing security issues and your standards for data encryption at rest and in transit?

Reading this brief set of examples, it’s clear that no one team can do this alone. Closing the gap requires investment, infrastructure, and standards that can be enforced across every product team.

Allowing each individual team to set or ignore these standards is a recipe for chaos. Imagine a scenario where one team considers a three-second page load acceptable, another targets five seconds, a third never defines a target and relies on skeleton loaders to tell the user that something is coming (eventually). Users will experience wildly different behaviour in different parts of the application, with no idea what to expect as they navigate through your system.

If Product doesn’t demand it, then it’s easy for these needs to continue to go unanswered. That’s a dereliction of duty by the product organisation.

Every time we ship without knowing whether our product will buckle under unpredictable load, when we only think about the cost of development and not the cost of ownership, we reinforce that features matter more than good product fundamentals.

We need to advocate for these benchmarks and enforce them, make their absence visible and surface the resulting risks. If your organisation doesn’t have such benchmarks, build alliances with engineering leadership and advocate for change. If your organisation does have them, don’t ship without ensuring you’re compliant. Pushing this into ‘technical debt’ is putting your competitive advantage and market position at risk.

We have to demand better. Our customers deserve it.

Closing the gap

Organisational benchmarks aren’t exciting. You’re unlikely to get plaudits for sharing uptimes at your next stakeholder review. Nobody really cares about the scaffolding until the building falls down.

But product management isn’t just about delivering what your users want. It’s also about making sure that you ship software that works. Make sure you’re measuring for both.

Hey, great read as always. You totally nailed it on the 'product failure' from neglected non-functional requirements. It's so true how easily reliablity becomes an afterthought. Sometimes I also think the pressure from stakeholders for new features makes it super hard to properly advocate for NFRs.