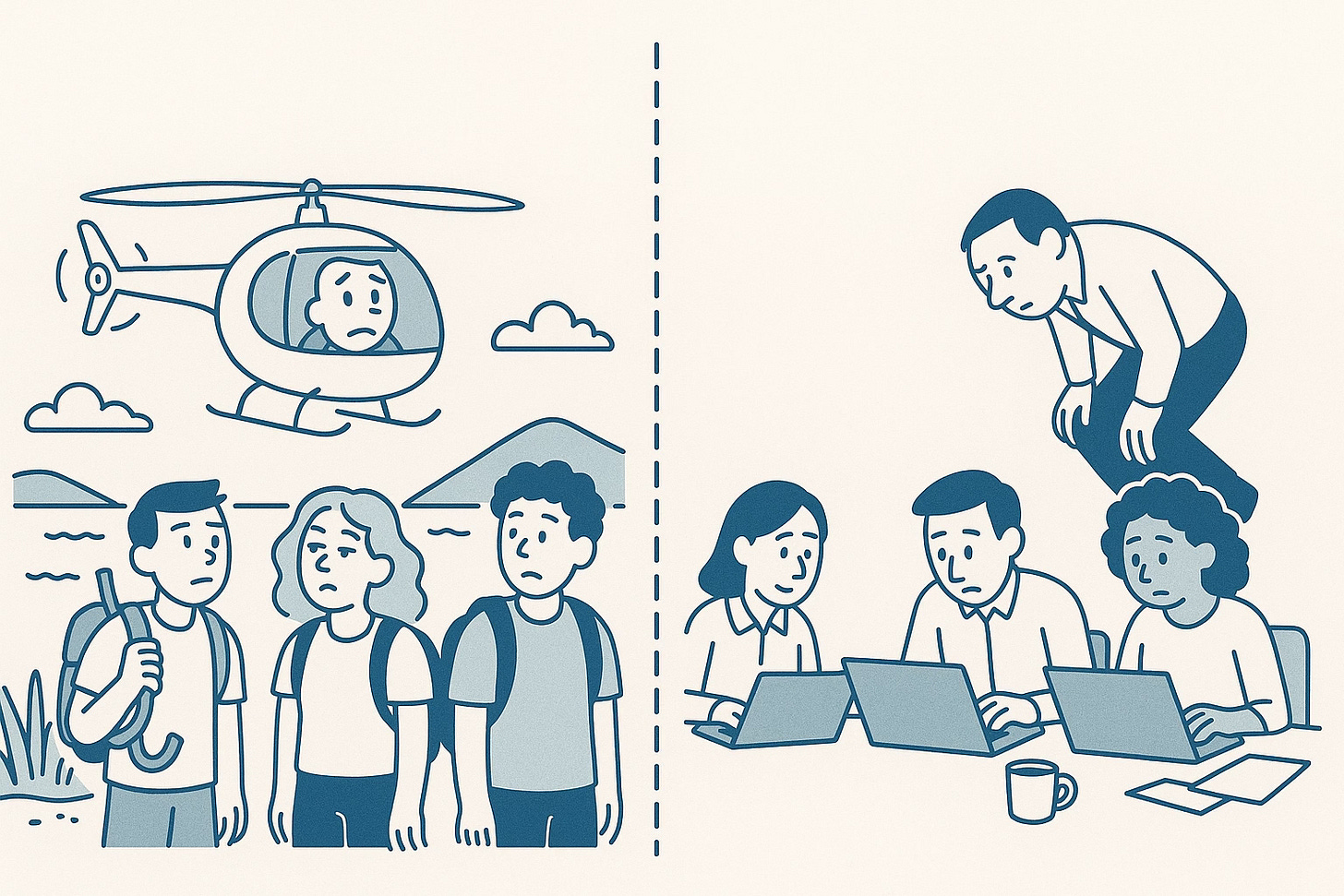

Helicopter bosses

Can't escape the searchlight? It might be time to change flight patterns.

All aboard

I spent eight years running an environmental education business. We partnered with schools and teachers to take middle and high school science and geography lessons out of the classroom and into the reefs and rainforests of Malaysia. Each programme created its own website documenting its discoveries. It was every bit as cool as it sounds.

We ran classroom sessions during term, and field trips during school breaks. We developed partnerships with schools and educators in China, Malaysia and the US. It was while establishing the programmes with our first partner schools that I first encountered helicopter parenting.

Helicopter parents hover over their children continuously, often stepping in to remove obstacles and protect them from hurtful experiences. While the parents’ heart is in the right place, helicopter parenting has been associated with increased anxiety and depression in children subjected to it, as well as a lack of independence.

The antics of some parents were amusing. They would book themselves into hotels in the same places we were running field trips, turn up at dive centres, and try to invite themselves along on activities. I never really considered it harmful - I always associated the anxiety more strongly with the parents than the kids, who seemed suitably embarrassed, but well-adjusted.

Flight patterns

Examples of helicopter parenting remained no more than funny anecdotes to be shared with friends until I realised that the same behaviour was now manifesting in the corporate world. As Covid took workers out of the office, managers fell out of their comfort zone.

“Research shows that managers who cannot “see” their direct reports sometimes struggle to trust that their employees are indeed working.” - Sharon K. Parker, Caroline Knight and Anita Keller, Remote Managers are Having Trust Issues, Harvard Business Review, July 2020

Even since return to office mandates have taken hold, helicopter management has continued and maybe even worsened. Micromanagement has always been with us, but the consistent beat of update requests feels faster than it ever was.

Like helicopter parents, leaders can insert themselves into their teams’ lives in unhelpful ways. They constantly look for updates (sometimes from several people at the same time) and override the team’s working processes, in a well-intentioned attempt to try to resolve blockers. Unfortunately for them, this stifles the team’s creativity and resilience, and can lead to learned helplessness and burnout. The non-stop requests for information prevent the team from having enough focus time and progressing with the work at hand.

This can lead to a vicious circle, where lack of progress results in more requested updates, which in turn prevents sufficient progress being made. Many managers fall into these patterns without realising it. Maybe they are under pressure from higher up the organisation, or it’s a particularly high-profile project that has the attention of the C-suite. We should have empathy for helicopter bosses. Helping them will help us all.

Signs you may be a helicopter boss

You have a number of daily update calls, where the update is ‘no update’ as the team hasn’t had a chance to do a sufficient amount of work. For example, you find yourself asking ‘what’s happening on the reporting feature?’ only to be told (again) ‘that’s with the platform team, and they’ve prioritised it for development next sprint, so, nothing to report there until they get started.’

You have (consciously or otherwise) inverted some of the tenets of the Agile Manifesto - for example you find yourself prizing adherence to a plan over learning and adaptation. Every deviation from a date suggested months ago is seen as a failure or cause for concern rather than a necessary refinement of how the team can achieve its objectives.

Your first answer to every question is ‘standardisation’ or ‘more process’ rather than giving the teams autonomy to solve their problems. For example, concern over teams’ velocity results in you asking for more frequent reporting against milestones instead of a diagnosis of what systemic issues cause friction for the team and thinking about how they can be removed.

Signs you have a helicopter boss

You read the above list and thought ‘I wish I could show my boss this.’

You wish you had time to think instead of constantly feeling you’re giving updates.

You have prep meetings for updates in your calendar more than once a week.

If you think you might be a helicopter boss

Ask yourself what you really need from the team to give you confidence in their progress? Can you get this without adding process or meetings to the calendar?

Consider the ceremonies that the teams already have for sharing information. Can you clearly explain why these are insufficient so that your reports can consider how to fill those gaps?

Can you take a step back? Do you need to be involved in the detail of the team’s work? What would it take for you to be able to elevate yourself above the fray but feel confident that progress is being made?

What data can you use that would allow you to monitor team progress without inserting yourself into their workflow? Would an asynchronous update or access to a burndown chart, deployment frequency, or cycle time work?

Think about trust. No, don’t roll your eyes. Really think about it. What is preventing you from trusting your teams? If you can’t answer this question, do you need to make changes to your personnel or structures so that you have more visibility? You may need to think about the impact your leadership style is having on those around you.

If you have a helicopter boss

Try to anticipate their needs. I have found that creating some reporting that answers the questions you’re likely to be asked puts everyone in a good place where the boss feels informed and the team autonomy is protected.

Think about the data you can share with them that will demonstrate progress. What will give them the comfort they need to allow you to progress without interruption?

Keep a log of interruptions. If you have a decent relationship with them, you can use this to campaign for a more structured communication channel, such as a weekly update.

Landing the bird

Those years taking students from reef to rainforest showed me that real growth happens when kids are given the space to explore and find things out for themselves within the constraints of a managed programme. They don’t need consistent monitoring but they do need structure and somewhere to go if things are off-track.

Teams have a similar pattern and set of needs. Success happens when everyone has the space to do their best work and the system surrounding them enables them to progress, and to raise the alarm if they are struggling.

In my experience, the best leaders know how to be present and offer support without needing to fix everything and prevent growth. This is the challenge for us all. Can we be the leaders our teams need so that we can all be successful and fulfilled?